By Kyle Osborn, Guest Author

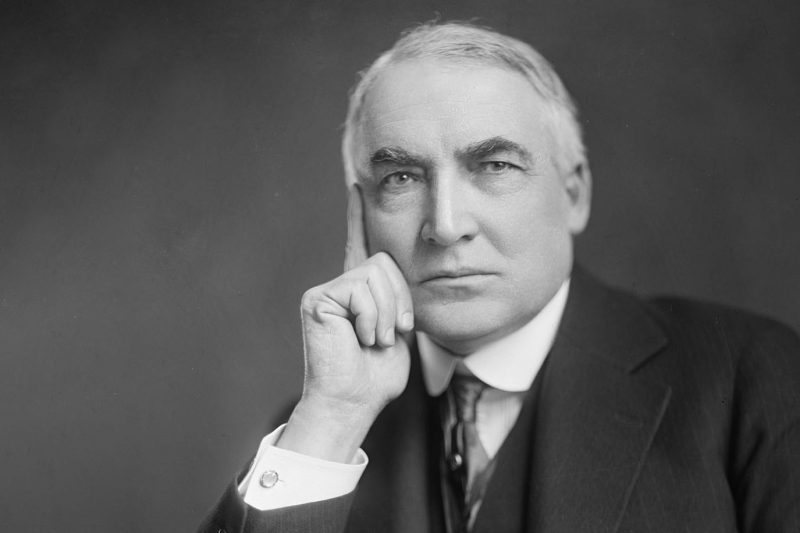

Americans take interest in their history during times of great desperation. Commentators have noted that the 2020 race eerily resembles that of a century before, the 1920 contest pitting Democrat James Cox against Republican Warren G. Harding. Being a stolid Midwesterner, Cox has all but been forgotten. No such luck for Harding, who regularly vies with Andrew Johnson for “worst president” in most historical polls. Consoling the anxieties of the American populace, his brilliant campaign in 1920 resulted in a landslide victory. Harding only lacked for substance as actual president.

The previous year, 1919, had been terrible. Already the 116,000 American dead from the Great War seemed like a sacrifice squandered. The United States had entangled itself in European disputes, the slaughter was without precedent (10 million soldiers killed), and the victorious Allies seemed far more interested in crushing Germany than in making “a world safe for democracy,” as President Wilson had promised. The rising sentiment of isolation was laid bare when the US Senate refused to join Wilson’s lofty League of Nations, an international organization aimed at securing global peace.

The domestic scene looked just as perilous. With war mobilization ending abruptly, the American economy crashed and unemployment soared. Labor strikes raged in startling size and ferocity. Americans confused the labor discontent with the radicalism of Europe – the Russian Revolution of 1917 had resulted in the world’s first Communist regime. A wave of anarchist bomb attacks killed very few but frightened many. Some American politicians called for sending subversives to island prison camps; many more called for limiting European immigration. An influenza pandemic had also reached U.S. shores. Derisively labeled the Spanish Flu (it probably originated in China, as if that matters), it killed hundreds of thousands of Americans, perhaps 60 million worldwide.

Race relations reached a nadir in 1919. The Great War promised economic opportunity and political freedom for African Americans, the majority of whom still labored in Southern sharecropping and under the shadow of Jim Crow. Starting the Great Migration, hundreds of thousands of African Americans fled the South for Northern cities, resulting in a violent racist backlash of ghastly proportions (at least 80 lynchings and 25 race riots in what became known as the “Red Summer”). The worst violence occurred in Chicago, where 38 people, mostly African-American, were killed.

And so Warren Harding invented a new word for the 1920 campaign – “normalcy.” Normalcy meant a return to an illusory past when such nightmares never existed. It meant isolation from the problems of Europe and its immigrants; it meant an end to the social experimentation of the Progressive Era; it meant a return to “law and order” (Calvin Coolidge was Harding’s 1920 running mate, famous for his hostility to labor strikes). America needed “not nostrums but normalcy,” Harding proclaimed, “not revolution but restoration.” Normalcy did not just win in 1920, it walloped – Harding coasted to the White House in one of the most one-sided victories in American history.

But slogans go only so far. Harding’s administration quickly mired itself in scandal – his Secretary of the Interior ended up in prison on corruption charges; his Attorney General resigned in disgrace. His economic policies did not deter the Great Depression, race relations were not addressed, and the anti-immigration/isolationist stances he began proved tragically impotent in the face of fascist aggression and Hitler’s murderous regime. Even Harding’s personal life seemed amiss. When he died in 1923, rumors circulated (falsely) that his wife had him poisoned in revenge for his extra-marital affairs (which were very true).

The moral is simple – vote on the substance, not the superficialities; vote for the candidate who addresses the real challenges of the present with the realistic policies those challenges require. It’s hard work digging underneath the gild and the glitter, but it’s the work that democracy demands. And if Harding is on the ticket, consider going the other way.

Click here to read another 2020 election-themed article written by professors at King University.

Kyle Osborn is an assistant professor of history at King University, where he has taught for six years. He received his Ph.D. in history from the University of Georgia in 2013 and his research focuses on the emotional experience of the American Civil War.

Click here to view all of the articles written by guest authors for The Kayseean.